It’s lonely in the future. Trust me, I’ve been there. For the last few weeks, I’ve been replaying Arkane Austin’s Prey, an immersive sim in which you explore a space station orbiting the moon. You’re trying to find out what went wrong – and why the whole place is overrun by hostile aliens. It’s an interesting tone, though. Despite the space station being hectic with nasty life, you spend a lot of time on your own – and yet that doesn’t mean there’s no sense of humanity to the game.

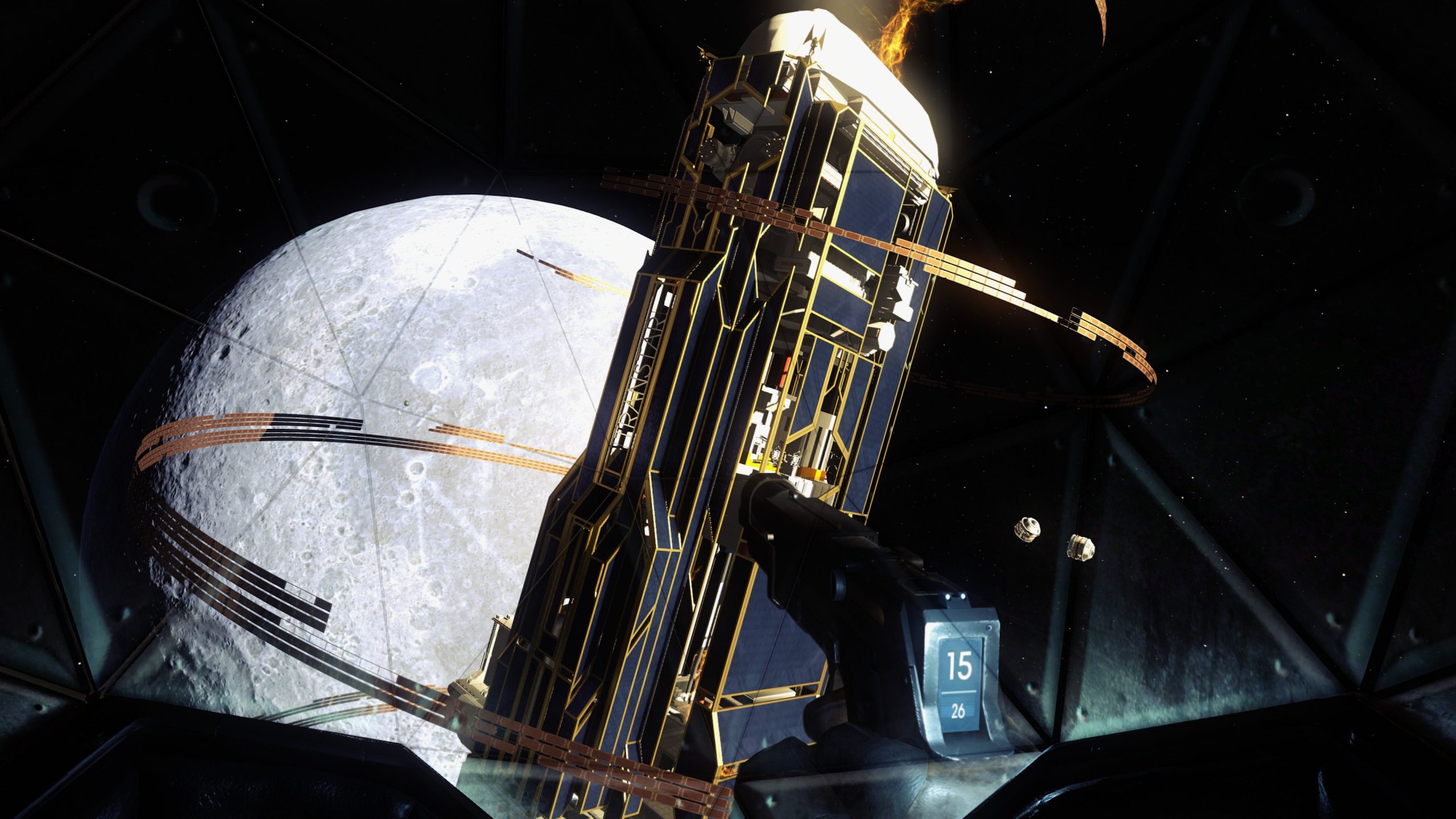

Sure, for the bulk of Prey’s runtime, interacting with other living people is a relative rarity, especially in the opening hours when anyone with a pulse who you happen to run into generally doesn’t remain that way for more than a few seconds. The advanced space station Talos I, once seen as a shining beacon of human brilliance and scientific advancement, now effectively serves as a floating prison for everyone trapped aboard, including main character and TranStar nepo-baby Morgan Yu. (TranStar is an unfettered ultra-capitalistic conglomerate on a quest to research alien creatures known as Typhon. Every sci-fi game needs a company like this.)

Let’s Play the First Hour of Prey Watch on YouTube

Because of this relative isolation, you learn more about the TranStar crew (largely consisting of scientists and engineers) by digging through their DMs like you’re the nosy parent of a teenager. Not just DMs, but emails, logs, reports, other written ephemera. Granted, this was hardly a new concept when Prey came out in 2017. It’s practically a staple in the immersive sim genre. What makes Prey special in this regard, though, is how its writing breathes rich life into characters before you have a chance to meet them.